Portrait of Faith Wilding. Photo by Karen Philipi.

Image courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi Gallery

In this captivating interview, Faith Wilding, a trailblazing artist who has left an indelible mark on the art world, engages in a thoughtful dialogue with three esteemed interviewers: Barret Lybbert, responsible for press and communications at the prestigious Anat Ebgi Gallery; Ashton Cooper, the Luce Curatorial Fellow at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, who brings a unique perspective with her curatorial expertise; and Rachel Elizabeth Jones, an artist and writer originally from Vermont, now residing in Los Angeles. Rachel's contributions to prominent publications and her explorations of folk traditions in her art, combined with her role as co-editor of tele- magazine and founder of Flower Head in 2020, make her a dynamic voice in this dialogue. Together, they explore the intricate intersections of feminism, folklore, nature, and mythology in Faith Wilding's artistry, providing invaluable insights into the artist's profound and influential legacy.

In this captivating interview, Faith Wilding, a trailblazing artist who has left an indelible mark on the art world, engages in a thoughtful dialogue with three esteemed interviewers: Barret Lybbert, responsible for press and communications at the prestigious Anat Ebgi Gallery; Ashton Cooper, the Luce Curatorial Fellow at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, who brings a unique perspective with her curatorial expertise; and Rachel Elizabeth Jones, an artist and writer originally from Vermont, now residing in Los Angeles. Rachel's contributions to prominent publications and her explorations of folk traditions in her art, combined with her role as co-editor of tele- magazine and founder of Flower Head in 2020, make her a dynamic voice in this dialogue. Together, they explore the intricate intersections of feminism, folklore, nature, and mythology in Faith Wilding's artistry, providing invaluable insights into the artist's profound and influential legacy.

This interview coincides with the highly anticipated release of the print edition, Three Dragons, One Goddess, created in partnership with Anat Ebgi Gallery, as we pay tribute to Faith's enduring legacy in the art world.

BL: Faith, let's begin by discussing your work, Three Dragons, One Goddess. This piece has become the foundation for a print edition that we've collaborated on with Exhibition A. Could you share some insights into the origins of this work and your recollections of its creation?

Faith Wilding's Print Edition Three Dragons, One Goddess

Faith Wilding's Print Edition Three Dragons, One Goddess

FW: (Laughs) It's quite kind of you to mention "initial recollections," considering I'm now 80 years old. (laughs)

REJ: I'm intrigued about the figures within the artwork and whether any particular mythologies influenced its creation.

FW: I grew up in South America, born in Paraguay. From a very young age, I loved fairy tales. My British family would send me beautiful books — "The Flower Fairies of the Wayside" and "The Flower Fairies of the Garden." I became obsessed with fairies, and the idea of fairies looking like flowers, living in flowers. During my time in Los Angeles, while studying at CalArts, I was heavily involved in feminist art communities - it was then that we debuted Womanhouse (1972)… This period also saw me doing a lot of research into goddesses and their historical context. I grew up in a Christian commune where we only heard of gods. Well – ONE god (laughs). My fascination with mythology remained strong, and my drawings of fairies evolved into goddesses once I became a strident feminist (laughs). This was coupled with extensive research into ancient art and iconic figures like the Venus of Willendorf. So, the goddesses stemmed from these influences, along with the realization that many feminists—and other people too—did not want to hear about the goddesses.

Faith Wilding Crocheted Environment, from Womanhouse, 1972

Image courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi Gallery

AC: That’s one element I feel particularly intrigued by. Faith, as you said, for some feminists, goddess imagery was incredibly foundational. I’m curious what continues to draw you to this subject matter and do you think it continues to teach us something in the present?

FW: I don’t know exactly why. Perhaps it's because I don't draw from "the figure" but from my imagination. The idea of a distinct female set of spirits always intrigued me and contrasted with the way I had grown up, where the whole idea of a mother or woman goddess was not entertained (laughs). I'm a bit of a rebel in that sense. The Venus of Willendorf—who knows whether she was perceived as a woman or a ‘Venus’ in her era. She’s a figure and that’s what fascinated me. This type of body, which represents an earth mother and inherently that means creation. It’s not a story about a male creator, but a female creator, making it a form of protest, from my perspective.

BL: Let's discuss the goddess's relationship with the dragons in your artwork. Are the dragons her creations? Do they coexist in a shared world?

FW: Dragons have always fascinated me, along with every fairy tale in existence. I'm also interested by archaeological digs conducted in various eras and locations, unearthing art and artifacts whose purposes remain uncertain... as a person, these aspects greatly interest me. Much of this information contradicts what I learned during my Christian upbringing, which was predominantly male-centered and paternal.

The exploration of women's power and how it has manifested across centuries and cultures in art is a central theme for me. I've traveled quite a bit, visiting archaeological museums whenever possible. I'm fascinated by the origins of everything, the grand narrative. What’s the long story? Through a feminist lens, what's women's role in this grand narrative? These questions inform my imagination and visual exploration.

REJ: Faith, hearing you mention this idea of the long story of feminism, delving into the past, considering our history… I often grapple with the binary of "nature is good" versus "technology is bad." How do you view technologies like artificial intelligence, and how do you think about technology contributing to a future that we actually want to live in?

FW: It's a complex matter. For me, the primary concern revolves around access to technology. Who can access it? Who understands it? Who has the power and resources to create it? The potential applications of many technologies aren’t things I want to support, for example, war and the ways in which machines contribute to power and its destructive potential. While curiosity is innately human, we must consider which communities are included in these dialogues and how they apply the knowledge they gain. For me, that’s the big question: how will the knowledge be used? Billions are spent on technologies that fuel conflicts in war-torn nations, while millions suffer in poverty. We’ll spend zillions of dollars to explore space but how much are we spending trying to help the poor, the wounded, and the disenfranchised?

REJ: I really appreciate that framework.

FW: When my art holds feminist or political undertones, it often revolves around nature and its significance. Why are we killing it? Why are we trying to modify it in such unproductive ways? This is how I think of my work being political — through a feminist reinterpretation of power dynamics and inequalities, questioning who possesses agency and resources. And, you know, I also really enjoy creativity and imagination, the joy of creating art. Maybe that’s why I keep doing it. I just like to use my imagination.

AC: Speaking of nature and the environment, you’ve referred to past bodies of work as “eco-feminist mythologies”. Can you talk about what that phrase means to you?

FW: To me, feminism has always been intertwined with an intense connection to nature. Both in terms of our environment and the essence of human nature and life. The need for ecological consciousness is only growing bigger. I’ve made a personal commitment to learn as much as possible about the current research of women scientists. This isn’t to say male scientists can’t be feminist ecologists. But I believe women's experiences and perspectives, considering their role in producing life, provide a unique viewpoint. In medieval paintings, the figure of Spring is often female. The figure of Mary, she represents birth. Women bring forth life, right? And yet, women's contributions were often sidelined, deemed to be their "role." Feminist ecology highlights that the role extends beyond giving birth, encompassing protection, engagement, preservation, and enhancement of life. This involves countering the “death drive:” the destructive urge to obliterate everything. While it's a collective responsibility to support the “life drive,” women often approach this task with great seriousness and feminists have really led that movement in many ways.

REJ: This ties in well with my next question. Faith, I’m curious what role do you think mythology and folklore can have today as we navigate an uncertain future?

FW: I think mythology and folklore play increasingly vital roles. Yet, our priority should be embracing life, connecting with those striving for existence worldwide. Technology doesn't necessarily favor struggling communities. Vast resources are poured into technology and war while hunger persists. We face daunting, scary times. I know there are many scientists attempting virtuous endeavors like, “how can we make more food”? “How can we teach gardening and help people grow their own food in a local, sustainable way”? But that’s not the main focus. The money invested into programs like that is tiny compared to what’s spent on AI technology.

BL: Navigating the future feels like venturing into uncharted territory, particularly in the realm of technology. What strikes me about your work, Faith, is how it anchors us in the ancient and eternal. You delve into folklore, mythologies, the arc of humanity, and remind us of the importance of rediscovering certain wisdom we might have overlooked.

FW: That’s nicely put. This resonates, especially since our society seems to be more on the side of culture than on the side of nature.

BL: Will you elaborate on what you mean by the distinction between culture and nature? Do you mean “culture” is what people create, and “nature” is what already exists?

FW: Essentially, yes. Nature for many people is a very distant experience. Many people today engage more with machines than nature. It's not that technology is bad —cell phones, for instance, connect us—but we must consider the cost. As technology advances, we risk overlooking fundamental aspects of life like air and plants. It’s a terrifying thought — how many people are more interested in making and maintaining fancy machines than making sure nature is protected.

BL: Faith, what potential do you envision in the process of us rediscovering a connection with our bodies as organic beings?

FW: Humans often overlook the need to preserve natural resources, assuming we can somehow just create replacements. There's a staggering amount of global extinction occurring, much of which remains unnoticed. You know, some tiny creature went extinct and the collective response is “who cares”, but then it turns out those little creatures had been tunneling in the earth to make air for root systems. A huge topic, right? I can’t cover it all in my work, but these are the thoughts I grapple with when creating; what I’m trying to figure out. Though I don’t think we should know everything because it's incredibly important to have wonder. When was the last time we truly felt wonder? Amid the wonder of machines, we should wonder at the sight of an exquisite flower. These are the essential human qualities that drive my work, qualities that have resonated with me since I was a small child, growing up in a tropical land full of all these amazing flowers and leaves.

BL: Circling back to Three Dragons, One Goddess, the work features a very pared down palette and I wonder what leads you to that kind of decision-making?

Faith Wilding's Print Edition Three Dragons, One Goddess

FW: It's vibrant, but simple. I love primary colors and watercolor — they're very transparent, easy to mix and blend. I love the accidents that happen. With watercolor, you have to learn how to produce accidents. Sometimes the accidents are really bad, but I remember after I finished that particular piece it was glowing. This piece also has gold leaf, which is a very tricky medium to work with. You can hardly breathe while you're working with it because everything’ll just fly off!

Faith Wilding Tentacular Wilderness, 2020

Watercolor, ink, colored pencil on paper, framed

29 x 21 inches / 73.7 x 53.3 cm

Image courtesy of the artist and Anat Ebgi Gallery

REJ: Faith, what role might art have as a tactic of survival now?

REJ: Faith, what role might art have as a tactic of survival now?

FW: I'm 80 years old, and I’m hopeful that art endures. There are hundreds of thousands of artists worldwide, and it’s comforting to think that their practice will continue and that artists will continue to reflect on their understanding of the world. Art is one of the things that makes us human.

REJ: Thank you. That's wonderful.

AC: It’s hopeful.

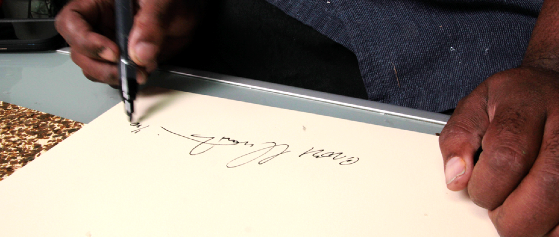

Faith Wilding signing her 2023 print edition Three Dragons, One Goddess