We asked the California-based artist a few questions about Tales, his 2023 solo exhibition at Shrine Los Angeles, the natural threads in his diverse body of work, and go deeper into the inherent mysteries of our 2022 collaboration Milk Heaven.

Tales, your recent solo exhibition at Shrine Los Angeles, featured your painting The Mays (pictured above), which Milk Heaven (pictured below) was based on. The exhibition explores the dimensional relevance of milk within this body of work. Both its material form and conceptual content is animalistic, evocative of nature’s soothing and nurturing qualities. Can you describe more about when you began incorporating the substance into your practice?

Milk is the most basic food for mammals. For the first part of our lives, we live on it. We are built from milk. It is a very pure food, because it is produced from the love of a mother for her child. It contains everything life needs: immunoglobulins, amino acids, etc. For me, painting is a way of making life. I like to feel life in the work, especially in this recent series of paintings. So it seems right to use the same materials that are used to create life. I’ve started to incorporate Italian egg tempera for this same reason. I like the alchemy of mixing these elements together with others — gold, graphite, trace minerals. Francis Bacon once said that art is all about a fascination with life. I think that’s true, though I like to think beyond the scientific definition of life. I’d rather see everything as alive. If I regard a rock or a car or my phone or even my knee cap as being inherently filled with life, everything feels better.

Milk Heaven, 2022

Unique series of 10 • 24k shell gold, milk paint, archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle hemp paper • 22.00 x 22.00 in / 55.88 x 55.88 cm

Collect Now

You’ve mentioned that Milk Heaven was created by “aiming for ecstasy” and incorporates a single secret phrase that was marked into the prints over a series of several months. I love text as a tool for obscuring legibility, trusting meaning is nevertheless perceived, sigil-esque. This technique also reminds me of Transcendental Meditation mantras, which are intended to be kept secret. Can you elaborate on your process for creating the Milk Heaven series?

Repetition is such an effective technique. It’s good for learning, training, and praying. Making art is already quite repetitive, and it’s a useful way to engage with the learning-training-praying qualities of repetition.

For instance, when I’m writing music, I listen to a composition hundreds of times over months, and then might perform it for many more years. As I do this, I’m putting those words and sounds into my body over and over and over again, far more than I tend to do with other people’s music. So what, exactly, am I putting in? When Bonnie Raitt sings “I Can’t Make You Love Me” for the thousandth time in her life, how is that song changing her?

I use music as an example because it’s so physical in the way it affects us, but you can apply the same thing to painting. If I work on a large, red painting for 3 months, staring deeply into it, moving a brush with the same hand, using the same kinds of short motions, what am I programming my body to do?

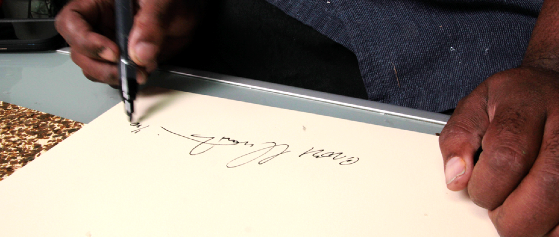

For me, writing a phrase repeatedly is one way of addressing this. Twombly was getting at that. J.B Murray too. I think of this phrase as a refrain. One painting could require thousands of refrains. Some drawings take only a few. Some of my shows are just one phrase repeated across many paintings. Other times a single painting holds many different phrases. It depends how long and how intensely I want to live with a phrase and what is the appropriate dosage for the situation.

With every repetition I’m pushing the language deeper inside of the subconscious. But If I speak it aloud or if the viewer can read the phrase, it returns to conscious reality again. So I transform this phrase into images that express it and lifeforms that give shape to it. This allows it to live beyond language.

Still from Simonini's music video I Am Love

Your practice seems to connect intimately with nature — whether it be the organic forms featured in your paintings, surrender to mindful awe in Milk Heaven, or the heavily mixed earthen media in your Books of Formation object series released around the same time as your novel The Book of Formation, Melville House Books, 2018. During our collective time of digital overload, what draws you into nature?

I grew up on the edge of a wilderness in California. A 1,514-acre state park started at the edge of my property. There wasn’t much else around, so I spent a lot of time playing in the trees. After I left home, I lived in cities for a long time and toured as a musician through other cities, but I eventually found myself overloading on concrete. My nervous system is better with wilderness nearby. So I stopped touring and moved to the countryside in California, to a town called Guerneville. I lived on the Russian River, in a redwood forest and then in Muir Beach for many years. This was necessary for a while. Now, I’ve been living in Altadena, which is on the border of the mountains and Los Angeles. I started an exhibition and concert space on my property. We can show paintings indoors and outdoors. It’s a good balance.

Ross Simonini